There are about 70 beatified or canonised Catholic martyrs associated with Oxford. Five of these were killed in Oxford and their stories are presented below. Out of the seventy, 4 were born in Oxford. Many of the martyrs studied at various colleges in Oxford:

St John's (8)

Trinity (7)

Brasenose (6)

Gloucester Hall [now Worcester] (5)

New College (4)

Exeter (3)

Oriel (3)

Corpus Christi (3)

Lincoln (2)

Hart Hall [now Hertford] (2)

St Mary Hall [now Oriel] (2)

Queen's (2)

Broadgates Hall [now Pembroke] (2)

Magdalen (2)

Christ Church (2)

Jesus (1)

St Edmund (1)

Balliol (1)

and Canterbury Hall [now Christ Church] (1)

Eight others are known to have studied in Oxford, but the exact colleges are unknown.

1. Bl Thomas Belson, layman; hanged 5 July 1589

The younger son of a well-known Catholic landowner of Buckinghamshire, Augustine Belson. Born in 1565 at Brill. His recusant father, when summoned to answer for his non-attendance at Anglican services, pleaded that he had no property to pay for fines although in the previous ten years he had defrayed the cost of sending Thomas to Exeter College, Oxford and Douai College, Rheims, to complete his education. Thomas returned to England in 1584. By June 1585 he was imprisoned in the Tower of London charged with 'conveying intelligence' for a Catholic priest, but he was released five months later on condition that he leave the country. Some time before 1589 Belson returned to Oxford, joining Fr George Nichols.

2. Bl George Nichols, Seminary priest; hanged, drawn and quartered 5 July 1589

A graduate of Brasenose College (1573), Nichols then taught at St Paul's School, London. After contacts with some Catholics in London, he was received into the Church. He went overseas, and enrolled at Douai College in 1581. Because he was known to be a pious, learned man already over thirty, he was ordained to the priesthood in September 1583, less than six months after his ordination to the diaconate. He studied for a further year at Rheims before returning on a mission to Oxford. The number of Catholics in Oxford was increasing rapidly. When a notorious highwayman, Robert Harcourt, expressed penitence, Nichols went in disguise to the prison garden on the morning appointed for Harcourt's execution and received him into the Church.

3. Bl Humphrey Pritchard, layman; hanged 5 July 1589

Humphrey Pritchard was a Welsh serving man who, by 1589, had been for twelve years in the employ of a Catholic widow, the proprietor of the Catherine Wheel Inn on St Giles', Oxford. The date and place of his birth are unknown, as is the name of the brave woman he served.

4. Bl Richard Yaxley, Seminary priest; hanged, drawn and quartered 5 July 1589 Yaxley was born in 1560 at Boston, Lincolnshire. He was enrolled at Rheims as a student on 29 August 1582 and ordained there in 1586, shortly before returning to England. He made his way to Oxford, stopping briefly at Denham to visit his college friend Bl Robert Dibdale, who was chaplain to a Catholic family until his own martyrdom at Tyburn in 1586.

Capture and martyrdomAll four men were apprehended at the Catherine Wheel Inn on St Giles', in Oxford (directly opposite the altar dedicated to St Catherine of Alexandria in the north-east corner of St Mary Magdalen church), which is now part of Balliol College. Spies had reported it to be the headquarters of Catholic activity in Oxford. Their pursuers first searched a house at Stanton St John belonging to Henry Rooke, a known priest-harbourer. Finding nothing, they returned to Oxford and at midnight, battered on the door of the Inn on St Giles', demanding admittance. The servant Pritchard was arrested when he unbarred the door, so the innkeeper requested a few minutes to dress and used the time to warn Belson, Nichols and Yaxley.

As there was no way for them to leave without being seen, they faced the intruders and answered their questions without giving grounds for suspicion. Not satisfied, the spy insisted on a search, and vestments were found. It was assumed that at least one of them must be a priest, so all three were arrested. The mistress of the inn and her servant Pritchard were also placed under arrest. By that time, friends and neighbours had congregated and obstructed the searchers by destroying some of the evidence.

The next day the five captives were interrogated by Martin Heton, Vice-Chancellor of the University, with other officials, including Lillie, Master of Balliol College, and Willis, President of St John's College. Nichols and Yaxley refused to admit their priesthood, hoping to protect their lay helpers from a charge of harbouring. When this failed, Nichols admitted his priesthood to shield the younger priest Yaxley. The lay people were confined in Oxford Castle and the priests in the old Bocardo prison at the north gate, where they were visited by Anglican clergymen who sought to engage them in theological argument. They were later taken in irons to Christ Church where they were questioned about other Catholics. When all refused to answer, the woman was bailed and the men were sent bound to London.

Pritchard was badly injured when his horse threw him, but the escort merely laughed and forced him to ride on. People living along the route came to see 'the monsters' they had been told to expect, but were amazed by their gentleness. A Magdalen postgraduate, Ellis, was so impressed by the cheerful behaviour of the prisoners that he rode beside them all the way to London. For this, and to prevent him from reporting the escort's cruelty, he was declared insane and committed to a madhouse for the rest of his life, even though many people confirmed that he was in his right mind.

Accused of being a traitor by the Privy Council, Nichols responded, 'I am here to teach the law of God, not to seduce people from their allegiance to the Queen.' He admitted his priesthood before the Council; Yaxley and Belson said only that they were gentlemen. The priests were then tortured in the Bridewell, being suspended from their hands for fifteen hours. During that time, they were identified as priests by two apostate priests.

To terrify Catholics and their sympathisers, the Council decided that the four men should be tried and executed in Oxford. They were transferred there by Sir Francis Knollys. On his arrival, Knollys summoned the innkeeper of the St Catherine's Wheel to answer her bail. She asked to be tried with the men, but he refused. Instead he confiscated all her property and sent her to prison for life. A carefully selected jury of convinced Protestants found the accused men guilty of treason. A scaffold was erected in the Town Ditch, where Broad Street now runs. On 5 July, Belson and Pritchard walked to it, but the two priests were dragged through the crowded streets tied to horse-drawn hurdles.

Fr Nichols was the first to be hanged, and was not allowed to speak. Silently he made the sign of the cross, mounted the ladder, raising the rope to his lips at each step and blessing it. Fr Yaxley, whose youth, good looks and noble bearing deeply moved the onlookers, did the same, kissed his friend's corpse and asked for his prayers. Belson followed, and lovingly clasped the two bodies before the ladder was taken away from under him.

Finally Pritchard mounted the scaffold and addressed the crowd, 'I beg all the people here present to bear witness, in this world and on the Day of Judgement, that I die because I am a Catholic, that is, a faithful Christian of Holy Church'. An Anglican minister exclaimed, 'Poor wretch, you say you die a Catholic, though in your ignorance you do not know what a Catholic means.' Pritchard replied, 'Though I may not be able to tell you in words what it means to be a Catholic, God knows my heart, and he knows that I believe all that the Holy Roman Church believes, and that which I am unable to explain in words I am here to explain and attest with my blood.'

When all four were dead, the priests' limbs were hacked off and exposed on the castle walls, where they were further mutilated with knives before being fixed to the town gates.

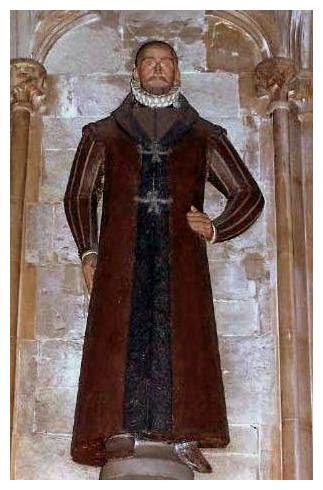

5. Bl George Napper, Seminary priest; hanged, drawn and quartered 9 November, 1610 Napper (or Napier) was born at Holywell Manor (now an annexe of Balliol College), Oxford in 1550, to Edward Napper (a Fellow of All Souls' College) and Anne Peto, the niece of William, Cardinal Peto. He entered Corpus Christi College in 1566, but was ejected in 1568 as a Catholic recusant. He visited Douai College eleven years later, but by December 1580 he had been arrested and imprisoned at Wood Street Counter, London. He was released in June 1589 when he acknowledged the Royal Supremacy. Napper entered Douai College in 1596, was ordained, and sent on a mission in 1603. On his return he lived for a time with his brother William at Holywell.

Early on the morning of 19 July 1610, he was arrested at Kirtlington, and a small reliquary and a pyx containing two unconsecrated altar breads were found on him. Napper was brought before Sir Francis Eure at Upper Heyford and searched thoroughly, and this further yielded a breviary, holy oils and a needle case. The possession of oils was held to be conclusive of his priesthood and he was condemned, but reprieved. Held at Oxford Castle, he reconciled a fellow prisoner named Falkner, and this was held to aggravate his crime. As he refused the Oath of Allegiance, he was condemned to death.

On 9 November, he celebrated Mass in the morning, and between one and two in the afternoon, he was hanged, drawn and quartered. His head was placed on the Tom Gateway at Christ Church, and his quarters on the four city gates. Some of the remains were removed secretly by his brother and buried in the chapel (later the barn) of Sanford Manor.

Some of the other martyrs associated with Oxford are:

Bl John Forest, priest, Franciscan o{ Greet avich Observant Friary. Studied at Greyfriars, Oxford.

Confessor to Queen Catherine of Aragon. Burned to death at Smithfield, London, 22 May 1538.

Bl Adrian Fortescue, layman, lay Dominica::. From Stonor Park, Oxford. Condemned by Bill of Attainder, untried. Beheaded at Tower Hill, London, 9 July 1539.

St Edmund Campion, priest, Jesuit. Born in London. Educated at Bluecoat School; scholar and fellow of St John's College, Oxford. After conversion, studied at Douai. Admitted to Society of Jesus at Rome in 1573. Ordained priest at Prague, 1578. Worked on the English mission June 1580-August 1581. Condemned for the fictitious plot at Rome, Rheims and elsewhere. Hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn, London, I December 1581.

Bl Thomas Pilcher, seminary priest. Born at Battle, Sussex. Studied at Balliol College. Converted, and studied at Rheims. Ordained priest at Laon m 1583. Worked on the mission in Hampshire and Dorset, 1583. Condemned for priesthood. Han/ed, drawn and quartered (aged 30) at Dorchester, 21 March 1587. No executioner could be found, so a butcher was persuaded to disembowel him, but stopped halfway, alarmed. The martyr (still conscious) asked gently, 'Is this your justice?'

Bl Stephen Rowsham (alias Rouse), seminary priest. Born in Oxfordshire. Studied at Oriel College, Oxford. Vicar of St Mary the Virgin, Oxford. L.onverted, and studied at Rheims. Ordained priest in 1582 at Soissons. Imprisoned soon after his return to England and banished; returned, and arrested again. Condemned for priesthood. Hanged, draw., and quartered at Gloucester, March 1587.

Bl Robert Sutton, seminary priest. Born at Burton-on-Trent, Staffordshire. Educated at Burton Grammar School and Christ Church College. Anglican minister of Lutterworth, Leicestershire. Apologised to his parishioners for having misled them for over five years, and declared his intention of becoming a Catholic. Converted, and studied at Douai and was ordained there in 1578. Worked on the mission in Staffordshire for nine years. Condemned for priesthood. Hanged, drawn and quartered at Stafford, 27 July 1588.

Bl William Davies, seminary priest. Born at Croes-yn-Eirias, Denbighshire. Studied at St Edmund Hall and Rheims, where he was ordained priest in 1585. Worked on the mission in North Wales. Condemned for priesthood. Compelled to attend Evensong during which he recited Vespers loudly and protested to the crowd that he 'would rather die than take part in an heretical service.' Hanged, drawn and quartered at Beaumaris, Anglesey, 27 July 1593.

Bl John Sugar {alias Cox), seminary priest. Born at Wombourne, near Wolverhampton, Staffordshire. Educated at St Mary Hall, Oxford. Left without taking the degree, not wishing to take the Oath of Supremacy. Convert Anglican minister of Cannock. Studied at Douai, where he was ordained priest in 1601. Worked on the mission in Warwickshire, Staffordshire and Worcestershire. Condemned for priesthood. Hanged, drawn and quartered at Warwick, 16 July 1604. On the scaffold, he reminded an attendant Anglican minister that the Catholic Faith was ancient but 'the new religion crept into the country in the time of Henry VIII'.

“ I have been long in durance and endured much, but the future reward makes pain

seem pleasure. And truly now the solitariness causes me not grief, but rather

joy, for thereby I can better prepare myself for that happy end for which I was

created and placed here by God. I am also sure that however few I see yet I am

not deserted, for ‘ whose companion is Christ is never alone.’ When I pray I

talk with God ; when I read He talketh to me. Thus, though I am bound and

chained with gyves, yet am I loose and unbound towards God, and it is better,

I deem, to have the body bound than the soul in bondage. I am threatened, Lord,

with danger of death ; but if it be no worse I will not wish it better. God

send me the grace, and then I weigh not what flesh and blood can do to me.

These answered many anxious and dangerous questions, but I trust with good

advisement, not offending my conscience. What will become of it God knows best,

to whose protection I commit you. From gaol and chains to the Kingdom. Thine to

life’s end.”—(Letter from prison.)

“ I have been long in durance and endured much, but the future reward makes pain

seem pleasure. And truly now the solitariness causes me not grief, but rather

joy, for thereby I can better prepare myself for that happy end for which I was

created and placed here by God. I am also sure that however few I see yet I am

not deserted, for ‘ whose companion is Christ is never alone.’ When I pray I

talk with God ; when I read He talketh to me. Thus, though I am bound and

chained with gyves, yet am I loose and unbound towards God, and it is better,

I deem, to have the body bound than the soul in bondage. I am threatened, Lord,

with danger of death ; but if it be no worse I will not wish it better. God

send me the grace, and then I weigh not what flesh and blood can do to me.

These answered many anxious and dangerous questions, but I trust with good

advisement, not offending my conscience. What will become of it God knows best,

to whose protection I commit you. From gaol and chains to the Kingdom. Thine to

life’s end.”—(Letter from prison.)